The Emperors of 55th Street

Written by Mark Schubin

If you’ve taken On Site Opera’s The Road We Came midtown tour, you’ve probably learned a lot about the two major opera companies that were once adjacent on the Lincoln Center Plaza. And you probably didn’t need the tour to learn that the Metropolitan Opera scheduled Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones, the first opera by a Black composer to be produced in the company’s history, as its 2021 opening night. Strangely, it’s not the first opera by a Black composer to be performed on the Met’s stage.

Today’s Metropolitan Opera Association, which came into existence in 1932, runs both the opera company and its opera house, but that wasn’t the case for much of the Metropolitan Opera’s history. When it was first organized in 1880 at Delmonico’s restaurant (shown at right in an image from King’s Handbook of New York City in 1893), it was as the Metropolitan Opera House Company Limited of New York.

Different opera companies were hired to perform in the building. After a fire in 1892, the organization that rebuilt the opera house was the Metropolitan Opera and Real Estate Company.

Like any other organization with an auditorium, the Met leased its theater when not using it. There was a pet dog show at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1899. Ballet companies often appeared.

The first female Black singer known to headline on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House was Billie Holiday at a jazz concert in 1944 (left), and Bert Williams and George Walker performed there in a gala in 1897. But opera was different. The Met did not want another opera company performing in its house.

When the National Negro Opera Company (NNOC) wanted to use the Metropolitan Opera House for a performance of Ouanga! by Black composer Clarence Cameron White in 1956, there was a great deal of negotiating before the Met allowed a semi-staged version. The last concession was permitting costumed dancers (shown at right a week before the performance in a portion of a photograph by Jerry Dantzic in The New York Times).

The Road We Came midtown tour notes that wasn’t the first time Black dancers had appeared on the Met’s stage. Baritone Lawrence Tibbett insisted Hemsley Winfield’s New Negro Art Theatre Dance Group be hired for a production of The Emperor Jones in 1933 (left); the Met had originally wanted to use white dancers in dark makeup as they had in a 1918 production of The Dance in Place Congo.

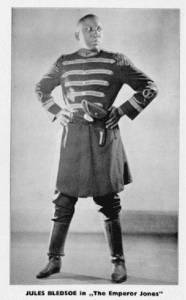

Winfield and his troupe were very well-reviewed. He died of pneumonia at age 26 before the end of the run. In many publications, Tibbett was also well-reviewed, but he was a white man performing in dark makeup (right). Vere E. Johns wrote in The New Age on January 14, 1933, “No greater bit of injustice has ever been done the Negro than the selecting of [Lawrence] Tibbett by the Metropolitan Opera Company to sing the role of ‘Emperor Jones’ at the Met. This, when we think of Paul Robeson, Jules Bledsoe and George Dewey Washington, each of whom would have surpassed Tibbett’s Performance.”

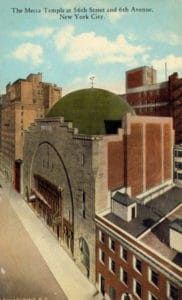

After performing Ouanga! on the Met stage, the NNOC took it to Carnegie Hall, another stop on the tour. The stage entrance of Carnegie Hall is on West 56th Street. Across the street and down the block is the stage entrance to what was called when it opened in 1925 the Mecca Temple of the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine. The order is known today as the Shriners, and the Mecca Temple, facing 55th Street (shown at left in a post card), is now the New York City Center.

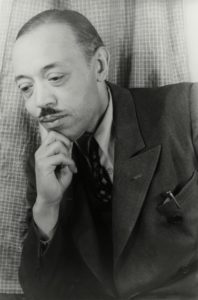

Black composer William Grant Still’s Troubled Island, mentioned on the tour, premiered at the City Center in 1949 in a New York City Opera production. Both that opera and Ouanga! are based on Jean-Jacques Dessalines, a leader of the Haitian revolution, later declared emperor. Still is shown at right in 1949 in a photograph by Carl Van Vechten.

NNOC was one of the longer-lasting Black opera companies (21 years). Opera Ebony, now based in New York, was founded in 1973 and is still going strong (one of its founders was involved in a production of Ouanga! in New Orleans in 1955). The Aeolian Opera Association was not so lucky.

Paul Robeson was the Emperor Jones in the play and movie. Jules Bledsoe performed the role in the play once, but he was the first Black singer to perform the role in the opera, beginning in Europe (left). He had written his own score before learning Eugene O’Neill had a deal with composer Louis Gruenberg; according to the Chicago Defender, Bledsoe’s was superior to Gruenberg’s. Returning from his successful European tour (of Gruenberg’s opera), Bledsoe joined the Aeolian Opera’s first presentation: Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana followed by The Emperor Jones at the Mecca Temple on July 10, 1934. Even the sets were those of the Dutch production.

Bledsoe and both productions got full houses and rave reviews for three nights. The Aeolian Opera had announced upcoming performances of Pagliacci, Rigoletto, Lakmé, and Carmen. Company founder Peter Creatore had covered the costs in the hope of finding more people to back the venture. He didn’t. The Aeolian Opera closed after its first double-bill production.

It’s impossible, of course, to squeeze every moment of Black music history in New York City into a single walking tour. On Site Opera’s three The Road We Came tours offer highlights that might inspire further research. And their moderately short lengths were designed with foot comfort in mind.