From “The Ear of Dionysius” To My Distant Love

Written by Mark Schubin

June of 2021 marks the first anniversary of On Site Opera’s singing-by-telephone production, To My Distant Love. What does that have to do with the artist Caravaggio, the physicist Charles Wheatstone, the author Victor Hugo, the engineer Nikola Tesla, the King of Portugal, and the Princess of Saxony? They were all involved in the centuries-long process of arranging to deliver opera by telephone.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, opera companies around the world were forced to cancel performances. On Site Opera came up with ways to continue paying artists without endangering anyone’s health, starting on June 18, 2020 with To My Distant Love (at right soprano Jennifer Zetlan performing by phone). It was so successful that its run was extended multiple times, and it was adopted by an opera company as far away as Melbourne, Australia. But it wasn’t exactly a new idea.

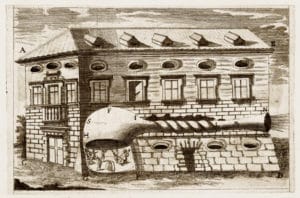

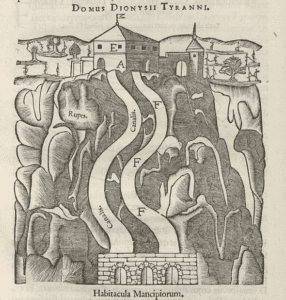

The first opera ticket was sold in 1637, and, with a now commercial endeavor, producers needed to maximize revenues and reduce expenses (“Of all the noises known to man, opera is the most expensive” is a saying attributed to Molière). Opera houses introduced boxes where the rich could see and be seen (for a fee) and had large capacities to help amortize costs. The original Italian word for opera, melodramma [musical theater], became the English “melodrama” because of the exaggerated gestures performers used to reach the farthest audience members. Kircher suggested using acoustic ducts to reach audiences beyond the opera house (above right), though he didn’t explain how that could be a revenue source.

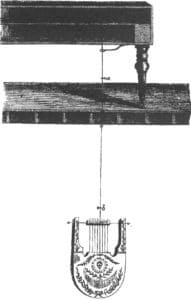

In 1787, after Paris got its first steam-powered water-distribution system, someone writing as M. Nicolas Tuyau (Mr. Nicholas Pipe) suggested using pipes to deliver opera music to homes by subscription. In London in 1821, a reporter attended one of physicist (and inventor of the concertina) Charles Wheatstone’s “enchanted lyre” concerts, in which a fake metal lyre (left), hung from a wire through the ceiling connected to the sound board of a piano on the floor above, emitted music; the reporter then suggested that a network of wires could be used to distribute opera music. And, in 1876, The New York Times suggested that people might rather listen at home to opera by telephone from the Academy of Music rather than “to go to Fourteenth street and to spend the evening in a hot and crowded building.”

Some of Alexander Graham Bell’s earliest telephone experiments, between Paris and Brantford, Ontario, in Canada, used a so-called “Triple” mouthpiece (right) for a trio of singers. His first demonstration of long-distance telephony involved sending the aria “Largo al factotum” from Rossini’s opera The Barber of Seville from Providence to an audience in Boston in 1877. The following year a complete opera was transmitted by wire in Bellinzona, Switzerland, and in 1880 bedridden former impresario Edward P. Fry listened to operas delivered from the Academy of Music in New York by telephone.

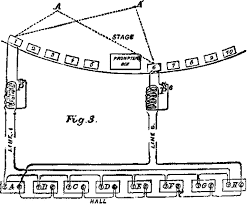

In 1881, the first International Electrical Congress was held in Paris. An aviation pioneer turned telephone experimenter, Clément Ader, ran lines from the main Paris opera house to the exhibition hall but added a twist, the world’s first demonstration of transmitted stereo sound. One of the listeners who pronounced himself and his grandchildren delighted with the effect was author Victor Hugo. The innovation was covered by many publications, including Scientific American (left) and Nature.

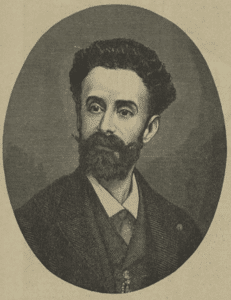

Meanwhile, Portuguese opera composer Augusto Machado (right) studied in France and wrote multiple works there for the stage. In 1883, his opera Lauriane became a big hit in Marseilles. He decided to bring it home the following year. The local-boy-makes-good story was front-page news in the Lisbon newspapers, and the king, Dom Luís, said he would attend the local opening performance. Unfortunately, between promise and premiere, the king’s sister, Maria Ana, Princess George of Saxony, died. Royal rules of mourning prevented the king from leaving the palace. The monarch was caught between honor and protocol.

Alan Danvers, manager of the local telephone company, recalled the 1881 Paris demonstrations and duplicated them in Lisbon. The king both stayed in his palace, as protocol demanded, and kept his promise to hear the Portuguese premiere of the opera (depicted at left in the publication O Antonio Maria). The king knighted Danvers, and two theatrical promoters wondered if there might be a business in delivering opera by telephone. They began offering the full Lisbon opera season the next fall.

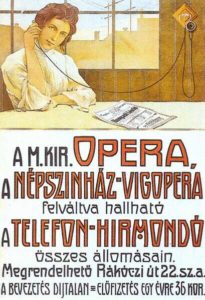

The idea quickly spread across Europe. In Madrid, where at the time there were only 80 telephone subscribers in the whole city, promoters planned telephone-listening halls. In Paris, there were coin-operated terminals in train stations and hotel lobbies and nicer facilities for home subscribers (who included composer Charles Gounod, author Marcel Proust, and the President of the Republic). In London, furniture was built with headphone hooks. In Budapest (poster at right), to maximize use of the lines, the world’s first newscasts were transmitted before the opera began; electrical visionary Nikola Tesla helped engineer the system, which stayed in operation from 1893 until the lines were bombed in World War II.

In Brussels, promoters sought to demonstrate their system by sending the aria “La donna è mobile” from Verdi’s opera Rigoletto from a concert hall to a booth at an electricity exhibition. Rights for the in-person performance were duly paid, but nothing covered the telephonic connection. Verdi sued and won in 1899, thereby establishing the principle of broadcast rights years before the first radio station went on the air.

On Site Opera’s production of To My Distant Love was done in honor of the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth. Two weeks before his death, Beethoven signed a petition to the German Parliament protesting illicit copying of printed music. Rest assured that On Site Opera’s telephonic transmission of his music occurred long after his rights expired.

To read more about To My Distant Love, click here.