She Paved The Way

Written by Mark Schubin

In ever-changing New York, it’s remarkable that the five stops on On Site Opera’s The Road We Came Lower Manhattan Tour remain largely as they were. Two other locations in the area, not stops on the tour but near the route, played a significant role in Black music history but are unrecognizable today. They are the sites of the last two concerts of the first U.S. tour by Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield.

She was born into enslavement on a plantation in Natchez, Mississippi. It’s not clear when she was born; different documents suggest 1817, 1819, or 1826. She received both her first and last names from the wife of her enslaver, Elizabeth Holliday Greenfield.

After the death of the plantation mistress’s first husband, Jesse Greenfield, and the divorce of her second, Elizabeth H. Greenfield moved to Philadelphia. The young girl, no longer enslaved, went with her. Elizabeth Taylor was her name when she was enrolled in Philadelphia’s Clarkson School.

The elder Greenfield provided for the younger in her will, but disputes prevented the latter from receiving any inheritance after the woman’s death in 1845, so Elizabeth T. Greenfield established herself as a music teacher. In 1851, she went to Buffalo, New York, where she performed at a soiree covered by the local press.

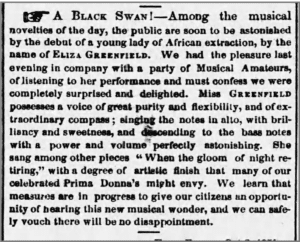

The most-famous singer in the U.S. at the time, thanks to promotion by showman P. T. Barnum, was soprano Jenny Lind, known as “the Swedish Nightingale.” Perhaps as an avian comparison, the Buffalo Commercial Advertiser headed its October 10 review of Greenfield’s performance “A Black Swan!” The description stuck. Black Swan Records, the first successful Black-owned label, was later named for her.

After a number of sold-out concerts in upstate New York, one with Lind’s piano accompanist, Greenfield took on Barnum associate James H. Wood as manager and embarked on a tour from Vermont to Wisconsin, including Toronto and Hamilton, Ontario, in Canada. She played at many of the same halls as Lind and stayed in many of the same accommodations. Lind heard Greenfield perform and encouraged her career. The last stop of the tour before Greenfield left for Europe was New York City.

Greenfield had frequently confounded her audience’s expectations. A review of one of her concerts in the Daily Free Democrat (Milwaukee) on April 21, 1852 said, “We see the face of the black woman, but we hear the voice of an angel.” Her repertoire was wide ranging. It included English, Irish, and Scottish ballads; opera arias by Balfe, Bellini, Donizetti, Verdi, and Zingarelli; an aria from Handel’s Messiah; a hymn, and other songs. She was said to have had an extraordinary vocal range. Sometimes she accompanied herself on piano.

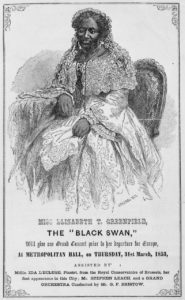

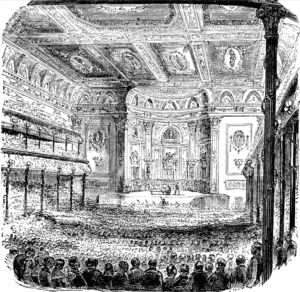

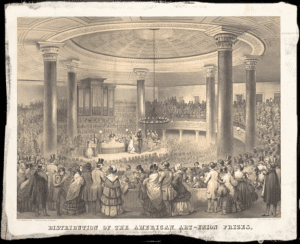

The poster for the concert at New York’s Metropolitan Hall (right) said nothing about audience restriction, but newspaper ads did: “No colored persons can be admitted, as there is no part of the house appropriated for them.” Even so, according to The New York Times the next day, “Several letters were sent to the manager threatening dire disasters to the building, if the dark lady were permitted to sing. Consequently there was a great parade of the Police force in the lobbies and in the body of the house. Fortunately, however, their services were not called into requisition.”

The Broadway Tabernacle closed in 1857, after being purchased by the Erie Railroad. Its site is now occupied by a nondescript apartment building called Saranac (right). The congregation still exists as the Broadway United Church of Christ on West 86th Street.

There is a small historical plaque on the Broadway façade of Hayden Hall. It commemorates the founding there of the American Society of Heating and Ventilating Engineers.

On Site Opera’s The Road We Came walking tours ensure that it’s not just engineers who try to inform the public of the histories of forgotten locations. The five stops on the Lower Manhattan tour and the other 11 stops on the Midtown and Harlem tours cover far more than just one person’s contribution to the history of Black music in New York City.