The Showboat: Made in NY

By Mark Schubin

On Site Opera’s musical performances aboard the Wavertree, a waterborne vessel, might suggest a showboat, and Show Boat (the novel, the movies, and the musical—the last performed by many opera companies) might suggest smoke billowing from tall stacks, paddle wheels churning the water, and music from the steam calliope calling audiences from miles around, on the bank of the Mississippi River at Natchez. But it was all born—smokestacks, paddlewheels, calliope, and on-board performances—on the banks of the Hudson and East rivers at New York City.

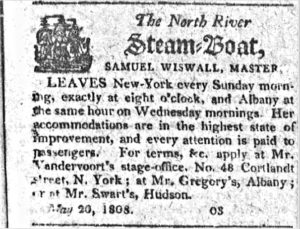

It began, perhaps, with Robert Fulton. In 1807, he launched a paddlewheel steamboat that made runs between New York City and Albany, with stops in between. The next year, rebuilt and expanded, it was the North River Steamboat of Claremont, the last word being the name of Fulton’s Hudson River estate. It wasn’t the first steamboat—it wasn’t even Fulton’s first—but a partner in the venture, Robert Livingston, obtained a monopoly on Hudson River steam navigation from the New York State legislature, and the vessel became the first steamboat to be commercially successful. A front-page ad from The Bee (Hudson, NY) is shown above left.

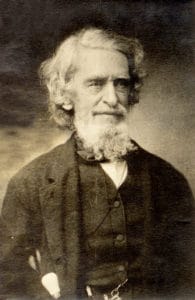

Next, perhaps, is Noah Ludlow (right). A large entry in the Encyclopedia of Alabama is devoted to him because he brought professional theater to what was then called the Southwest frontier, territory west of Georgia. Born in New York City in 1795, Ludlow moved to Albany and took his chances traveling with a theatrical troupe told it would be welcomed in Kentucky. Ludlow went ahead of the others, arranging for performance spaces in ten New York State towns before reaching Olean in July 1815. There he bought a sort of flat barge on which the troupe could float downriver, first to Pittsburgh and then on to Kentucky. Vessels of that sort were commonly called arks at the time, so this one became Noah’s Ark.

There’s no known indication that performances were ever given on that boat (though lines were recited on it), but Ludlow’s autobiography notes that, in his travels, he “beheld a large flat boat with a rude kind of house built upon it having a ridge roof above which projected a staff with a flag attached upon which was plainly visible the word Theatre.” That vessel left Pittsburgh in 1831, carrying the Chapman acting family, late of New York City, and they did perform for paying audiences on board their floating playhouse. When they reached New Orleans, they sold the boat, secured transportation north, and started again. One of the floating theaters is shown in a contemporary sketch above left. Eventually, they could afford a powered vessel.

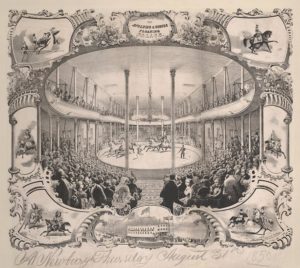

The first Chapman showboat was 100’ long and 14’ wide. One of the largest showboats ever was the Floating Palace (right), built in the early 1850s by Gilbert Spalding to show off the equestrian shows of his partner Charles Rogers. It had a museum as well as a large auditorium with a full-size circus ring. It has been reported to have been as much as 250’ long and 60’ wide, with a seating capacity of 3,400 on two levels. Spalding, known as “Doc,” had been an Albany, NY, pharmacist, and his Floating Palace was almost certainly influenced by the floating museum, menagerie, and theater of Henry Butler, launched on the Erie Canal in 1836.

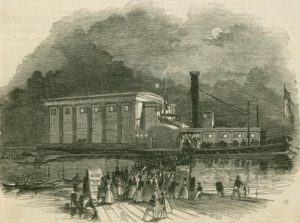

Meanwhile, the Chapmans returned to New York City, where “opera barges” were plying the waterfront. They purchased the Virginia, a coastal paddle-wheel freighter built in 1817, and had it rebuilt as the Temple of the Muses (shown at left from an article in the Illustrated London News). Relaunched in 1845, it had a full-size theater, dressing rooms, backstage areas, orchestra pit, and on-board gas plant to feed a brilliant limelight mounted on a tall mast so audience members could see where it was berthed that night. It plied the New York waterfront in both the Hudson and East Rivers, perhaps even where the Wavertree now floats, before bringing performances to Long Island Sound and upstate. It was the progenitor of the steam-powered showboat (and it also spawned copycats on New York’s waters).

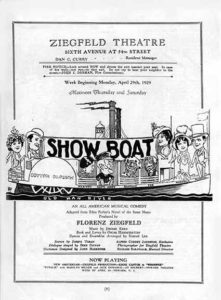

Edna Ferber, author of the novel Show Boat, lived at 65th Street and Central Park West and did the research for her book on an east coast showboat. Jerome Kern & Oscar Hammerstein II, who came up with the musical Show Boat (1929 ad shown at right) were both native New Yorkers. That doesn’t mean there weren’t showboats on the lower Mississippi River, but, as in the setting of Show Boat, their heyday started much later in the 19th century.

One was run by Callie Leach French (shown at left around 1890). Long after retiring in 1907, she was inducted into various maritime and river halls of fame because she was the first woman to earn both a pilot’s and a master’s license. In decades of moving showboats along the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, she never once had an accident (her last boat was destroyed in a crash shortly after she sold it).

In addition to her duties as pilot and master, “Aunt Callie” cooked, acted, wrote jokes, nursed the ill and injured, and laundered and sewed costumes. A fine musician, she also played both for the shows and, to let people know the showboat was coming into town, on the steam calliope.

That instrument, audible for miles, was first introduced on a New York City tugboat, the Union, and its first sale was in 1856 to the Glen Cove, a passenger vessel making the Hudson River run between New York City and Albany. It was powered by live steam from the boiler, so, to avoid being scalded, French played her keyboard in heavy gloves.

On Site Opera’s performances on the Wavertree continue a long tradition of music on the waterfront of New York City. Fortunately, today’s musicians needn’t play in heavy gloves.