The First Black Opera Recordings

By Mark Schubin

The Harlem walking tour of On Site Opera’s The Road We Came exploration of Black history in New York City ends at 226 West 138th Street, the former home of James Williams, chief of the Red Caps of Grand Central Terminal. That might not seem to have much connection to the first Black opera recordings, but it does.

Perhaps it would be best to start earlier. When Thomas Edison came up with his first phonograph in 1877, music ranked low on his list of its uses. That changed when soprano Marie Rôze sang an aria from Gounod’s Faust into the device in 1878. An engraving of the event was front-page news and became the image of the phonograph.

There had been opera recordings in France in 1860; “La Chanson de l’Abeille” [“the bee song”], from Victor Massé’s opera La Reine Topaze [The Topaz Queen], was captured twice on Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville’s phonautographe. The system was intended for sound analysis, and it wasn’t until the 21st century that technology became available to play the recordings.

As commercial recordings became available, opera was considered highly desirable. On the largest illuminated sign of its time, the Victor Talking Machine Company advertised that they could deliver “The Opera at Home.” One of their recordings of Enrico Caruso singing “Vesti la giubba” [“Put on the costume”] from Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci [Clowns] is considered the earliest recording eventually to sell a million copies.

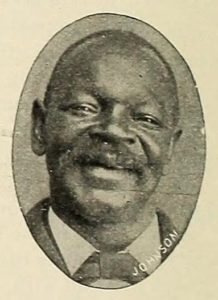

Black performers were also involved in the early recording industry. George W. Johnson, shown at left in a photo from The Phonoscope in July 1898, was recorded beginning in 1890 and was distributed by the three largest record companies — Columbia, Edison, and Victor — as well as many smaller ones. He’s considered the first Black commercial recording artist. Black comedians were also popular; Bert Williams, who had performed with his partner George Walker at a gala at the Metropolitan Opera in 1897 to raise money for the poor, was considered the most popular Black recording artist prior to 1920. But what they recorded was about as far from opera as could be imagined.

Across the street from Chief James Williams’s house in Harlem, the last stop on the On Site Opera tour, was Williams’s neighbor, friend, and brother Elk, Harry Pace. It’s worth noting that the Elks organization to which they belonged was the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks of the World, formed in 1897 because the original Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, formed in 1868, excluded Black members until 1972.

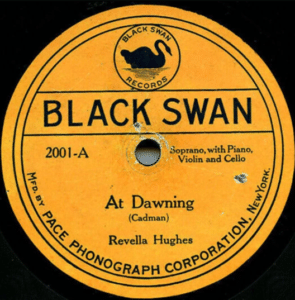

Pace, who had studied and worked with W. E. B. Du Bois, formed a record company in 1921 with the intention of releasing uplifting work. Du Bois suggested he name it Black Swan Records in honor of the Black concert singer Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, known as the Black Swan. The first two Black Swan records were of soprano Revella Hughes singing “At Dawning,” a song by American opera composer Charles Wakefield Cadman, and baritone C. Carroll Clark singing “For All Eternity,” an English translation of “Eternamente” by Italian opera composer Angelo Mascheroni.

Sales were not sufficient to keep the company afloat. But shortly before Black Swan Records was created, blues composer Perry Bradford convinced Okeh Records to record and release Mamie Smith singing “Harlem Blues.” According to Bradford, the company was threatened with a boycott if they recorded a Black woman, so he acceded to their request to change the title of the piece to “Crazy Blues.” It became a huge hit. Pace noticed and recorded Ethel Waters singing the blues. The ensuing success was sufficient to save the company and allow Black Swan to release what was probably the first opera recording by a Black female artist, “Caro nome” [“Dear Name”], from Verdi’s Rigoletto, sung by soprano Antoinette Garnes, in 1923.

Black Swan has been called the first Black-owned record company; it wasn’t. It was the first with wide distribution, the first to be successful (at least for a time), and the first major one, but there were at least two that came before. One was Broome Special Phonograph Records, which, beginning in 1919, released such Black artists as Harry T. Burleigh, Florence Cole Talbert, and Clarence Cameron White, whose later-composed Ouanga! won the American Opera Society’s award for best American opera and was the first opera by a Black composer performed on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House (but not by the Metropolitan Opera Company). It appears that the full Broome output is not known, but what is known doesn’t include opera.

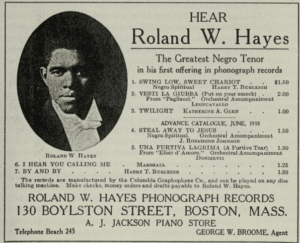

Before starting his own record company, however, George W. Broome worked as agent for another Black-owned record company, one with the purpose of releasing recordings of just one artist: Roland W. Hayes. Some sources say that, at his peak in the 1920s, Hayes was the world’s highest-paid singer; when he started out, he had to rent his own singing venues and arrange to record his own records. At left is an ad he ran in May 1918 in the program of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The second record listed is the same opera aria that became Caruso’s million seller.

Hayes crossed paths with Chief James Williams, whose former home is the last stop on On Site Opera’s Harlem tour of The Road We Came, later the same year. Both were at Carnegie Hall for a benefit performance for the Circle for Negro War Relief. And there’s another On Site Opera connection to Black Swan Records. A composer who “never wearied of playing, over and over,… Black Swan records I had purchased in a little shop in Harlem” was Darius Milhaud, whose The Guilty Mother was produced by On Site Opera in 2017.